Resuscitation for the Masses: How the Invention of CPR Shifted the Line between Life and Death

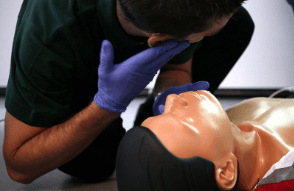

In 1960, the Journal of the American Medical Association published a manuscript credited with saving more lives than any other medical article of the previous hundred years.CPR training using a life-saving mannequin

Modestly titled “Closed-Chest Cardiac Massage,” it described a simple method of keeping alive people in cardiac arrest. “Anyone, anywhere, can now initiate cardiac resuscitative procedures,” the manuscript’s authors wrote. “All that is needed are two hands.”

By pairing their new technique of closed-chest heart massage with mouth-to-mouth artificial respiration, W.B. Kouwenhoven, James Jude, and G. Guy Knickerbocker braided together two separate threads of resuscitative medicine that had been under investigation for years. During the closing decades of the nineteenth century, researchers had tried closed-chest heart compression on animals and humans, but the technique did not gain a clinical foothold.

Meanwhile, surgeons reported success with open-chest heart massage — seizing the heart and squeezing it to restore circulation — as early as 1901. Physicians coupled this emergency technique with electrical defibrillation by the mid-twentieth century.

Artificial respiration boasts an even longer history. William Tossach described a mouth-to-mouth method in 1744, but the later discovery of elevated levels of carbon dioxide in exhaled air gave rise to a fear of using it in resuscitation. For more than a century, efforts to mechanically compress the chest to restore breathing were common. James Elam at last confirmed in 1954 that mouth-transmitted air could safely maintain respiration.

Four years later, Kouwenhoven and Knickerbocker were studying closed-chest defibrillation when they noticed that the heavy electrodes they were using on a dog compressed the chest and caused an increase in arterial blood pressure. They wondered whether rhythmically applying pressure to the chest could maintain blood circulation.

Working with Jude, they soon discovered that using two hands to press down the sternum compressed the still or fibrillating heart and forced blood out from it. Repeated once or more per second, the process could keep blood circulating in the victim until defibrillation equipment was available or the patient could be transported to a hospital.

It was a seemingly miraculous transformation of the boundary between life and death.

In a 1960 presentation at the Maryland Medical Society, the JAMA authors and James Elam declared that closed-chest heart massage and mouth-to-mouth ventilation “cannot be considered any longer as separate units, but as parts of a whole and complete approach to resuscitation.” This merging created cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) as we know it today.

In a half century, CPR has revolutionized resuscitative medicine and spread around the world. Millions of Americans receive CPR training every year, often making bystanders the first defense against sudden cardiac arrest.

* * *

Please note: I have previously written about the history of CPR for Proto magazine.