There’s Gold in That Medicine

Gold has real medicinal value. It is used in implanted devices like pacemakers, and of course in dental work. Some people believe a controversial liquid suspension called colloidal gold may have uses in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and in the delivery of tiny amounts of medications.

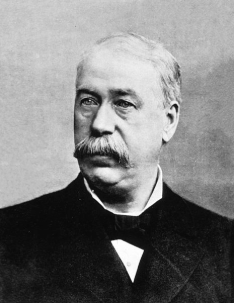

But of all the medical uses involving gold and the fortunes built from them, perhaps the strangest belonged to Leslie M. Keeley, a nineteenth-century physician who convinced countless desperate people to take gold as a remedy for addictions. Keeley’s supposed gold-based therapy for alcoholism and drug dependency launched dozens of treatment centers around the U.S. and made him rich.

Keeley, who had previously doctored Civil War troops as a member of the Union Army medical corps, first combined the special ingredients of his “Bichloride of Gold” nostrum in 1880 and declared it a cure for chemical addictions of all kinds. Over the next 11 years, he developed a marketing scheme for the compound and opened the first Keeley Institute in Dwight, Illinois. By 1900, the year of Keeley’s death, there were Keeley Institutes in every state. Keeley hit upon his claimed cure at an opportune time when other treatment choices for alcohol and drug addicts offered little genuine chance for recovery. Some quack potions were actually loaded with as much as 48 percent alcohol — that’s 96 proof.

Keeley’s cure thrived for a time because it offered the credibility of a pseudoscientific explanation for addiction. He declared that alcoholism resulted from damage to nerve cells that weakened the victim’s will power. Patients could lose their craving for alcohol and drugs only if they underwent treatment to purge their cells of poisons and restore them to proper functioning. Teamed with rest, exercise, and healthy food, draughts and injections of Keeley’s gold formulation could eliminate the addiction, he said.

Scientists responded that there was no such thing as “Bichloride of Gold.” Skilled marketing and testimonials drowned out the objectors. Patients typically spent four weeks in residence at one of the Institutes, resting, eating, and receiving daily doses of Keeley’s medicine. Anyone who completed treatment was called a “graduate” and could join one of the Keeley Leagues that sprang up around the country.

Over the years, an estimated 400,000 people underwent the gold treatment at a Keeley Institute. Keeley’s staff claimed a cure rate of 95 percent but acknowledged that a few people resisted healing. “Such a case no more affects the merits of the Keeley treatment than does a spiritual backslider affect the power and good of religion,” promotional literature pointed out.

Although the Keeley Institute in Dwight remained open until 1966, the credibility of the treatment faded long before that. A 1907 lawsuit had exposed the actual ingredients of the Gold Cure compound: strychnine, atropine (the drug ophthalmologists use to dilate pupils), boric acid, water — and no gold, in “bichloride” form or otherwise. Keeley was not only a quack — though he deserves some credit for treating alcoholism as a disease instead of a moral failing — but also a purveyor of fool’s gold.

[I have adapted this post from an article I previously wrote for The Saturday Evening Post.]