Wilde in the Streets

Here I present an oldie — an article I wrote 25 years ago for Minneapolis-St. Paul Magazine. It was one of my first attempts to write about history and has always remained among my favorite stories because of the unflappable character of Oscar Wilde. Note how the narrative approaches but skirts around Wilde’s homosexuality. Otherwise, I hope the article still stands up.

When the flamboyant Oscar Wilde visited Minneapolis-St. Paul in 1882, old-world aestheticism met Midwestern earthiness head on

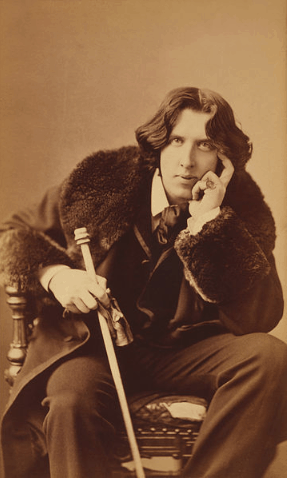

Late in the afternoon on March 15, 1882, a striking-looking visitor stepped off a train at the main rail station in Minneapolis. Six feet, three inches tall, he had shoulder-length brown hair parted in the middle and a pale, putty-like complexion. His slouch hat and green, fur-trimmed coat drew some attention, but he most impressed a growing crowd of gawkers with his behavior. “Oscar Wilde, photographed in New York City in 1882. (U.S. Library of Congress) He shuffled languidly along the platform to the carriage, seemingly afraid that he might fall in pieces;’ a reporter for the Minneapolis Journal observed. The visitor was a famous Irish-born wit and man of letters. His name was Oscar Wilde.

Wilde had not yet written The Importance of Being Earnest, The Picture of Dorian Gray or any of his celebrated literary works. Nor had he yet served time in a British prison for sodomy. When he arrived in the Twin Cities Wilde was the author of a single volume of poetry and an unproduced play.

He had already gained notoriety in Britain, however, as an epigrammatic advocate of art and beauty. He and other members of a much-mocked aesthetics movement in England advanced the then-unmasculine notion that only beauty was worth living for. Lampooned for the long periods he spent gazing rapturously at flowers and other beautiful objects, Wilde believed that art should be enjoyed for its own sake.

A bizarre chain of events brought Wilde and his then-outlandish aesthetic ideas to Minnesota. A London producer named D’Oyly Carte wanted to send Patience, the newest opera by Gilbert and Sullivan, on an American tour. One of the show’s main characters is Reginald Bunthorne, a “fleshy poet” and phony aesthete partly modeled after Wilde. Carte feared that the comic effect of Bunthorne would be lost on an American public unfamiliar with the affected mannerisms of Wilde and his cronies. Carte’s solution was to ask Wilde to tour America in advance of the opera.

Dazzled by promised fees of $200 to $1,000 per lecture (a range equivalent to $4,500 to $18,000 in 2012 dollars), Wilde consented. He arrived in New York on Jan. 2, 1882, and created an immediate sensation with his witticisms and languid poses. When a customs officer asked if he had anything to declare, Wilde replied, “Nothing, nothing except my genius.” Journalists both loved and hated him; they found him deliciously quotable yet suspiciously effeminate.

Wilde lectured in New York City and, riding a wave of Anglomania, moved on to engagements in Boston, Cleveland, Detroit, Cincinnati, St. Louis and Chicago. Americans perplexed him. “Everybody seems in a hurry to catch a train,” he said. “This is a state of things which is not favorable to poetry or romance.” In Indianapolis he angered a group of farmers by calling them “the peasants of this young and undeveloped country.”

By the time Wilde reached the Twin Cities he had abandoned his plans to break ground for Patience. (The opera premiered in St. Paul two months before his arrival.) Signing the register as “Oscar Wilde and servant, of England,” he booked into the Nicollet House hotel.

Even before his arrival the Twin Cities press targeted him for ridicule, mocked his mannered way of speaking and likened him to a sideshow exhibit. “Oscar is the best advertised menagerie this country has ever enjoyed….This utterly, all but entirely if too too concentrated young man has secured more gratuitous notoriety than any Wilde animal which has heretofore landed on these hospitable shores,” the St. Paul Globe sniped. The St. Paul Pioneer Press called his appearance “a farce; and since nobody can be deceived, everybody is happy while the receipts come in handsomely.”

On the evening of his arrival, Wilde granted an interview to a reporter from the Minneapolis Tribune. Speaking with his interrogator while reclining on a fur robe, Wilde cut the figure of a perfect dandy. His black velvet coat, tight pantaloons, patent-leather shoes and blue cravat made as unfavorable an impression on the reporter as his condescending comments about American art. “The fact that he was slightly pigeon toed,” he reporter noted, “detracted somewhat from his lion like appearance;’ The interview was published under the headline, ”An Ass-Thete.”

Later in the evening a crowd of about 250 (mostly women) assembled at the Academy of Music in Minneapolis for Wilde’s lecture on the decorative arts. Tickets cost 75 and 80 cents. Two chairs and a table supporting a glass of water stood before a backdrop which one observer called “one of the most outrageously inartistic and utterly vulgar sets from the scenery at the academy.”

“Everybody seems in a hurry to catch a train,” Wilde said. “This is a state of things which is not favorable to poetry or romance.”

Wilde appeared on stage shortly after 8 p.m. He wore an old-fashioned outfit of knee breeches, black silk stockings, shoes with large bows and a coat adorned with lace cuffs. Some jeers floated down from the gallery, but Wilde ignored them.

The oration quickly bored most people in the audience. Wilde’s suggestion to combine beauty with utility in everyday objects met with apathy. Reviews called the lecture “a series of artistic platitudes” and “as flat and insipid as could well be imagined.” His heavily accented and monotonous voice further distanced him from the audience, giving, said one reporter, “the impression that he was a prize monkey wound up and warranted to talk for an hour and a half without stopping.”

Wilde in fact spoke for 75 minutes. At the end of the lecture he bobbed his head and abruptly left the stage. There was no applause. Nevertheless, the crowd was not completely dissatisfied. “I came to see Wilde, and I have seen him,” a member of the audience said. “I did not expect to learn and did not.”

Richer by $250, Wilde returned to the Nicollet House at 9:25. A curious crowd awaited him at the hotel, but in true celebrity fashion he slipped in through a service entrance.

Perhaps due to its large Irish population, St. Paul was more cordial to Wilde. At times it was almost too friendly. While walking along a street Wilde was startled by a passing streetcar driver who called out, “Hey Oscar!”

Adding a kid glove and a lace handkerchief to his attire, Wilde repeated his decorative-arts lecture on March 16 at St. Paul’s Opera House. This time he spoke more engagingly and before a bigger audience. He upbraided the city’s citizens for the mud in their streets and the ugly furniture in their hotels. Expecting a different sort of performance, one man left the lecture moments after its start, exclaiming loudly, “I thought this was a theayter!”

Wilde returned to the Opera House on the next day for St. Paul’s celebration of St. Patrick’s Day. When a speaker lauded Wilde’s mother, an Irish patriot, the huge crowd cheered. In appreciation Wilde delivered a speech praising Irish culture.

With no further public appearances, Wilde left the Twin Cities for Iowa and points west. By the end of his U.S. tour in July he had lectured on beauty and aesthetics 75 times in halls from Manhattan to California.

Wilde’s lasting impression on Minnesotans squared with their perception of him as an amusing freak. For the remainder of the year Oscar Wilde costumes were the rage at parties. A Christmas masquerade held in the town of Dodge Center in 1882 featured a guest who, according to a newspaper account, represented Wilde in “knee breeches, big buckled shoes, [and] low collar…and got around with the esthetic languid air of the champion of lahdadahism in a style that was button-bursting to see.”

Wilde, in turn, drew conclusions about Minnesotans and their fellow Americans. “The Americans are not uncivilized, as they are so often said to be,” he wrote to the actress Sarah Bernhardt. “They are decivilized.”