A set of dusty boxes: The arresting origins of The Nazi and the Psychiatrist

My book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist has just been published. It had strange beginnings.

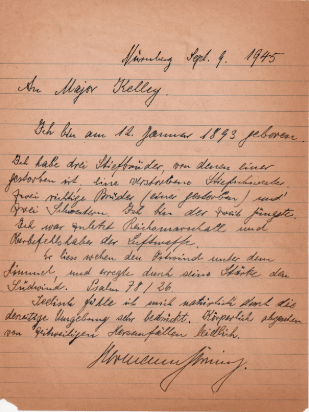

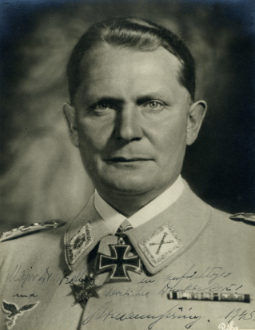

When one dead man passes you a tip about another, you pay attention. Years ago, while researching my book The Lobotomist about Walter Freeman, the psychiatrist and neurologist who pioneered lobotomy for mentally ill patients, I read the late Dr. Freeman’s writings on a topic that obsessed him: psychiatrists who commit suicide. One Douglas M. Kelley, MD — once famous for his study of the top Nazi prisoners held for trial at Nuremberg — received special attention from Freeman. The portrait that Göring signed to Kelley. On New Years Day in 1958, Kelley inexplicably swallowed cyanide and suffered an excruciating death in front of his wife, sons, daughter, and father-in-law. Nobody could understand why a man in the prime of life, famous and engaged in his work, had decided to end things so violently. The Nazi who had most powerfully drawn Kelley, Hitler’s prospective successor Hermann Göring, had killed himself the same way to cheat the Allied hangman.

I couldn’t forget about Kelley. Four years after reading about the psychiatrist, I tracked down his oldest son, who invited me to stop by and look at some of his father’s papers. I couldn’t believe what awaited me — a collection of astounding manuscripts from Dr. Kelley’s files. The boxes had come from the Santa Barbara home of Dukie Kelley, the psychiatrist’s widow, who had died a few months earlier, aged 92. Kelley’s son led me to four boxes that stood separate from the rest. “These are his Nuremberg papers,” he said.

I removed one lid, and the first thing I saw was an old Kodak carton labeled in hand, “X-Rays of Hitler’s Skull.” There were eight large transparencies inside, all showing different radiological views of a skull topping a spinal column. As sometimes happens in x-ray pictures, a faint presence of fleshy body outlined the bones. This was Hitler’s head. “Dad got those from one of Hitler’s physicians,” the son said.

Beneath the Kodak box was a priceless collection of Nazi and Nuremberg mementoes. They were more than mere memorabilia — they represented the sum of Kelley’s psychiatric involvement with some of the worst criminals in history. The son left me there for a couple of hours to go through the collection as a changing guard of cats watched disdainfully from nearby recliners.

The top file said “Goering.” I opened it and met the Nazi face-to-face. He stared out in his Luftwaffe uniform from a framed photograph: a big black military cross was fastened between the lapels of his collar, and an eagle clutching a swastika lifted its wings on his breast. Stormy clouds brewed in the studio background behind his head. Göring’s hair shone with highlights and he was not smiling. “Major Dr. Kelley,” the India-ink inscription began. There was a seven-word message in German, which I could not read, followed by a grandiloquent signature and “1945.”

Much more filled the Göring file. Scribbled letters, still in their envelopes from his wife and daughter, responded to messages he had sent from prison. A leather-bound notebook detailed Kelley’s many physical and psychiatric examinations of the prisoner. Kelley had also written a lengthy interpretation of the Rorschach inkblot tests he had given to Göring and the other top Nazis. Scraps of paper written in Göring’s hand filled the file, some in English requesting Kelley’s presence in the prisoner’s cell “immediately” or “at once.”

Beneath Göring’s file lay small boxes, the size of necklace cases. They contained peculiar jewels. In one were six paper packets, still sealed with smears of red wax. Each contained samples of sugar, chocolate, and other foodstuffs that Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess had refused to eat in prison because he believed they were poisoned. Hess signed and dated each packet and wrote an explanation of his suspicions. Another little box enclosed a bed of cotton wool upon which lay a glass vial of about a hundred white tablets: the narcotic paracodeine. The prison authorities seized these from Göring soon after his capture. He had been addicted to the drug.

I took photos of these items, partly to keep my hands busy and to distance myself from the thoughts pressing on me: What on earth were these artifacts doing in a ragged cardboard box that was sitting on the floor of a modest living room? Why weren’t they in the collection of an archive devoted to the history of the Nuremberg Trials? Clearly no historian of the trials or the Third Reich had ever set eyes upon them, so what was I doing holding these objects in my hands?

I did not want to consider the answers to these questions at that moment, or the nagging realization that these bankers’ boxes held documents and artifacts of inestimable historic value, because three more cartons still remained for me to go through. It’s a poor excuse for rushing through a trove of valuable documents, I know, but I had to get back to my mother’s house for dinner before rushing off to the airport.

I did my best. The cats circled and licked themselves. Kelley’s son clacked away at his computer in the next room. I inhaled dust, flakes of paper, and particles of a dead Nazi leader’s paracodeine stash.

When I returned home, I frequently thought about the boxes I left behind. Kelley’s son promised to save them for me in case I wished to come back and look at them again. I did so wish, and I returned soon and often. My new book, The Nazi and the Psychiatrist, grew out of them.