A virtual funeral changes perspective

An eminent neuroscientist died last week at the age of 95. He made important discoveries and helped countless people with complicated medical conditions. But he died during the COVID-19 pandemic in a state with many sick people, was denied a public burial, and his family planned a virtual funeral.

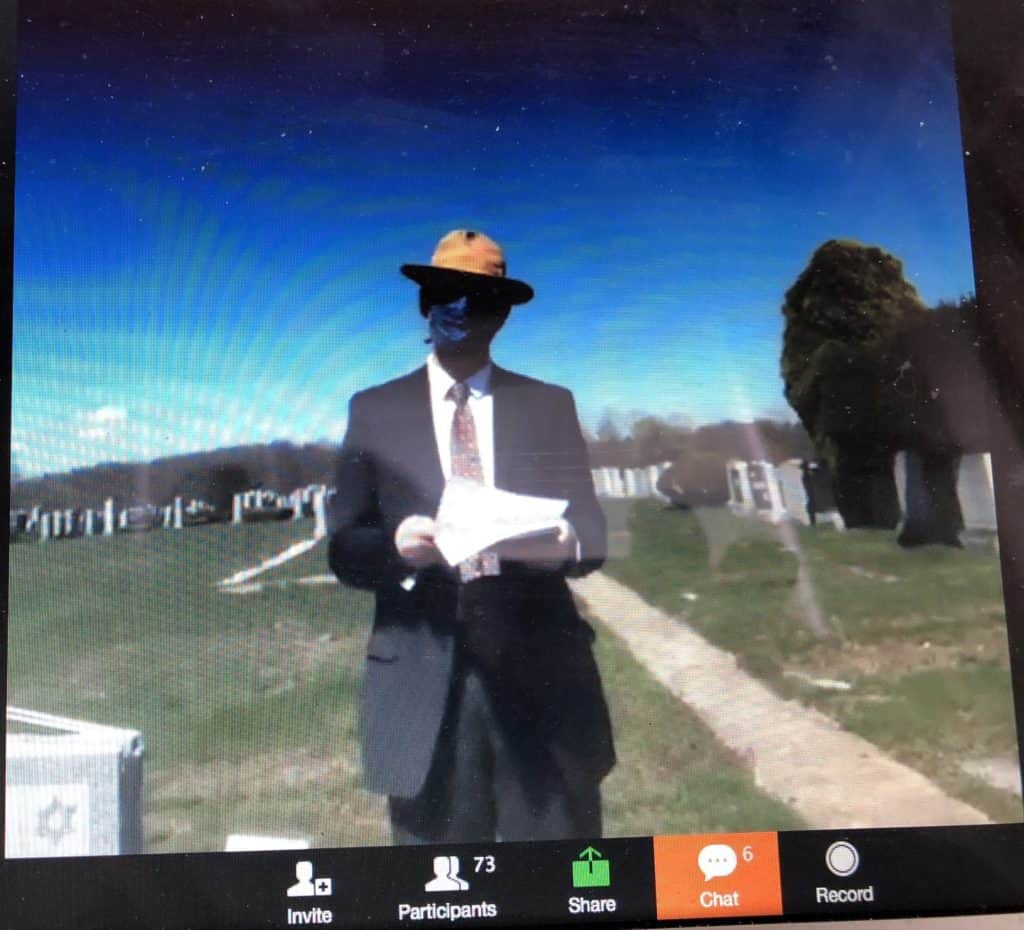

This was my first time attending a virtual funeral. I wondered what it would feel like to observe through a tiny lens a man’s passing into whatever follows our lives. Nobody would be at the cemetery except a rabbi and a funeral home employee holding a smart-phone camera. Another 75 of us, scattered around the world, would click onto Zoom to watch on screens of various sizes.

Unmuted mourning

For ten minutes my Zoom screen was grey, awaiting the start by the host. Then suddenly the rectangle burst into a churn of images: a casket draped in an American flag beneath a clean, cloudless sky; a gallery of corners and ceilings of living rooms and dens, along with faces of my fellow mourners; a uniformed soldier folding the flag. Scrambled voices mingled with Taps and the pleas of a host to mute or stay quiet.

Those who didn’t mute – the attendees were mostly elderly and unfamiliar with the technology – often replaced the cemetery at the center of the screen whenever they spoke or coughed. We all saw them in close-up, with sadness, perplexity, and anticipation on their faces.

At one point, a drawing appeared on the screen showing a half-naked woman astride a motorcycle. A mourner apologized: “I’m using my granddaughter’s laptop and I don’t know what I’m doing. It’s her screen picture.”

With birds chirping in the background, the rabbi willed himself to the center of the screen and began the graveside prayers. He wore a face mask, black for the occasion, covering everything below his eyes.

His masked face brought concern. Voices cut in and faces flickered. The sky behind him was so blue. An aged woman appeared on the screen, her face distorted as she peered into her screen using a large magnifying glass.

With no family at the graveside, no tent to block the sun, no sobs or sniffles, the rabbi continued to the eulogy. He knew the man well as a scientist, friend, and wise man. The deceased had continued skiing into his mid eighties. He loved his family. The rabbi noted the irony of family members being unable to gather in person precisely when they needed most to do so. The wind scratched against the smart-phone’s microphone.

The elderly woman set aside her magnifying glass and looked up at the ceiling. She spoke something softly. Was she feeling sadness or release? I could not tell.

Group prayer

The rabbi urged others to join him and began reciting the mourner’s kaddish. From my laptop’s speakers came a group murmur bathed in static, and there was a flash of faces. Many of the expressions were childlike, suggesting awe.

The service ended when the rabbi tossed a handful of dirt on the casket, said it would be lowered into the grave at a later time, and thanked everyone for watching. The screen went black except for a gallery of faces, maybe 30 of them still remaining, at the top. These people did not know what to do next. They peered at their screens, saw the other faces, and waited for something to happen. Someone typed a chat message: “God bless a great man and his wonderful family.”

Then something did happen. A tone split the silence and an attendee received a phone call. She conversed about the service we had all just seen. The drawn faces in the gallery tilted their heads as they listened.

That’s when I felt close to my fellow mourners. I glimpsed the wonder, confusion, and curiosity they betrayed sitting in the private rooms of their own homes. Many would have been stone-faced at the cemetery. Here they acted like themselves. More than any in-person burial I had ever attended, this virtual funeral was more clearly about the survivors than the dead.

I hit “end meeting,” blinked to awareness in my own home, and wondered what my next virtual funeral would bring. I knew there would be more of them.