U.S. Supreme Court Decides Whether the Tomato is Fruit or Vegetable

All of last week’s attention on the U.S. Supreme Court reminded me of an earlier decision that was downright pedestrian compared with the court’s judgment on healthcare law. The big legal question in Nix v. Hedden (1893) was whether federal law should view tomatoes as vegetables or fruits.Fruit or vegetable? The Supreme Court had an opinion.

How the tomato — that luscious outgrowth of the plant in the nightshade family known to botanists as Solanum lycopersicum — made it to the docket of the Supreme Court is a juicy saga that begins in the early decades of the 19th century.

Southern tomato growers had built a lucrative trade in shipping their produce to customers in the northern states. When the Civil War interrupted this commerce, Northerners began importing tomatoes, as well as other vegetables, from Bermuda and the Bahamas. After the war ended, Southern growers wanted their business back. They pressured the federal government to slap a tariff on imported vegetables, and in 1883 Congress at last complied.

The Tariff Act of 1883 imposed a tax on imported “vegetables in their natural state, or in salt or brine, not specially enumerated or provided for in this act, ten per centum ad valorem.” Specifically exempted from the 10 percent importation duty were “fruits, green, ripe or dried.” While the new law pleased the tomato cultivators, it upset importers. In 1886 prominent produce wholesalers John Nix and Company of New York City cooked up a plot to make pulp of the tariff law.

Seeds of dispute

That spring, Nix ordered a shipment of green tomatoes from Bermuda. The company paid the importation tax and began drawing up a lawsuit against the U.S. government official responsible for enforcing tariff duties at the Port of New York. When Nix filed its lawsuit in 1887, the case began its catsup-slow progress through the legal system that would culminate in the Supreme Court’s decision.

This was the same fruit of the vine formerly known as the “love apple,” was it not?

The lawsuit made an early stop in the court of Emile Lacombe, a judge of the U.S. Circuit Court for the Southern District of New York. The plaintiffs asserted that since tomatoes were fruits by botanical definition — the ovary, with seeds, of a flowering plant — the Tariff Act should not apply in this case. In support, the Nix attorneys read into the record a variety of dictionary definitions of “fruit” and “vegetable,” which established that vegetables were horticulturally considered the edible leaves, stems, and roots of plants. Next came testimony from New York City produce sellers — undoubtedly Nix friends and associates — who agreed with the dictionary definitions. “I understand that the term ‘fruit’ is applied in trade only to such plants or parts of plants as contain the seeds,” one swore. Concluding the plaintiff’s case, the Nix lawyers read to the court dictionary definitions of “tomato.” This was the same fruit of the vine formerly known as the “love apple,” was it not?

The U.S. attorneys representing Port Collector Hedden continued on a similar note. They read aloud dictionary definitions of “pea,” “eggplant,” “cucumber,” “squash,” and “pepper” — all examples of produce commonly regarded as vegetables even though botanists consider them fruit. Should the court then exempt them from the provisions of the Tariff Act of 1883?

The dictionary pages kept rustling. The plaintiffs counter-argued that no botanical confusion existed for the vast majority of vegetables, and proceeded to read out the definitions of “potato,” “turnip,” “parsnip,” “cauliflower,” “cabbage,” and “carrot.” By the end of these presentations, everyone in court must have wanted to break for salad.

After stewing over the testimony and evidence, Judge Lacombe issued his ruling on May 14, 1889. He cited earlier cases in which technical definitions of terms were determined to be different from commonly accepted meanings. He found that “the word ‘vegetable,’ in its popular and received meaning, is used to cover a class of articles which includes tomatoes, and the word ‘fruit,’ irrespective of what the dictionaries may lay down as to its botanical or technical meaning, is not in common speech used to cover tomatoes. For these reasons I shall direct a verdict in favor of the defendant.”

It was a serious setback for Nix, not to mention to the science of botany. The company vowed to appeal the decision. In doing so, it added fuel to a conflict that still rages today: the clash between botanical, horticultural, and cultural definitions of foods.

Overlapping categories

Fruits and vegetables, as it turns out, are not mutually exclusive categories. “The tomato is unquestionably a fruit botanically, but it is also considered a vegetable,” says Craig Andersen, extension horticulture specialist for vegetables at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. Tomatoes, as well as cucumbers, squash, peppers, and other produce botanically classified as fruits, are dual citizens — vegetables by custom and tradition. The fruit-vegetable divide, however, exists only in our minds, not in nature.

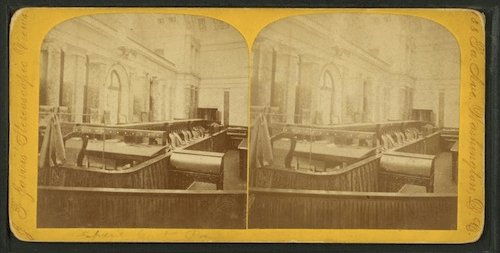

Which was exactly the point the U.S. Supreme Court focused upon after Nix appealed its case all the way to the highest court in the land. Nix v. Hedden reached the Supreme Court during the 1892-93 session. Citing a case from 1889, Robertson v. Salomon, Justice Horace Gray wearily noted that the Court had been down this road before. In that decision, Justice Joseph Bradley had written an opinion establishing that for the government’s purposes, beans were vegetables, not seeds.

To resolve Nix v. Hedden, Gray believed, the botanical description of tomatoes was irrelevant. Furthermore, dictionary definitions offered no legal evidence. What mattered to Gray were the commonly understood meanings of “fruit” and “vegetable”: the definitions likely to be in the minds of the congressional representatives who passed the Tariff Act of 1883. “These [dictionary] definitions have no tendency to show that tomatoes are ‘fruit,’ as distinguished from ‘vegetables,’ in common speech, or within the meaning of the tariff act.” In other words, although tomatoes may scientifically be fruits, there is an alternative world of common perception in which they are more accurately considered vegetables. Thus the Supreme Court went on the record as a classifier of tomatoes, and it refused to overturn the decision of Circuit Court Judge Lacombe. The Nix scheme to sink the tariff failed.

Recent tomato controversies

The provisions of the Tariff Act of 1883 long ago faded from practice and memory. Yet the decision of the Supreme Court justices in Nix v. Hedden, as well as Justice Gray’s written opinion, still resonates — even though botanists continue to regard tomatoes as fruits. In 2003, the New Jersey Legislature convulsed in controversy when a representative proposed to make the Jersey tomato the state fruit. A better-organized contingent rallied around the high-bush blueberry, which eventually won the designation. Two years later, tomato advocates tried again, this time advancing the tomato as the state vegetable. Supporters of Assembly Bill No. 3766 specifically cited Nix v. Hedden in their assertion that it was no mistake to call the tomato a vegetable. (Arkansas avoided this horticultural row by designating the tomato the state fruit and vegetable.)

So by legislative act and the opinions of some of America’s distinguished legal minds, it is safe to call the tomato a vegetable. Botanists still remember this slight. “They took and applied the culinary usage and totally ignored the science purely to get more tax money,” horticulture specialist Andersen complains. “Somebody did not grease the right palms.”

[Much of this essay previously appeared in an article I wrote for The History Channel Magazine.]