A Political Warning from the Past

Decades after a U.S. Army psychiatrist who studied the Nazis predicted a threat to American democracy, we should remember his fears when we vote.

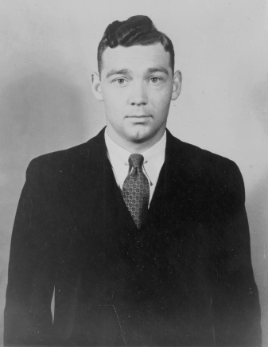

Psychiatrist and U.S. Army Lt. Col. Douglas M. Kelley returned home in 1946 after spending six months studying the most loathsome of the captured German leaders after World War II. I tell his full story in my book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist.

He was afraid. Kelley, who had served among the prisoners as a staff physician at the Nuremberg jail before and during the celebrated international tribunal that charged 22 top Nazis with war crimes and crimes against humanity, didn’t fear for the fate of Germany or Europe. He agonized over the future of America.

As we hit the final hours of another political campaign season in our country, one in which citizens will vote to fill 36 gubernatorial and 33 U.S. Senate seats as well as countless local offices, it is time to reexamine the concerns of a young psychiatrist who looked into the souls of some of history’s greatest sociopaths who rose to positions of power. These men thought nothing of using the Gestapo, concentration camps, racist laws, murder and the Holocaust for their own political gain.

How did these Germans attain political power? Were they mad? What motivated them? Kelley’s disturbing conclusions still resonate today. And he despaired of the American voter’s ability to resist the rhetoric of aspiring despots. Attack ads, attempts to demonize opponents, appeals to the irrational fears of voters, and the low level of discourse in political debates — all hallmarks of today’s campaigning — would convince Kelley that many Americans of 2014 are ready to vote for candidates more interested in climbing to power than working for the public good.

Sane and manipulative

“There wasn’t an insane Joe in the crowd,” Kelley said of the Nazi leaders when The New Yorker profiled him in 1946. Instead, they represented a personality type easily found everywhere in many walks of life: ambitious climbers, eager for power and influence and skilled at tugging at the emotions and fears of others to get what they wanted. These are the people we all know who keep their eyes on the prize as they walk upon the backs of others. They “are not unique people,” Kelley told lecture audiences. It’s normal to find them around us.

In politics, candidates of this type use “the rights of democracy in anti-democratic fashion,” Kelley observed. While many Americans believe that in our country the few cannot control the many and our democratic traditions will not tolerate totalitarianism, Kelley declared such optimism naive. He found ample evidence that candidates routinely pander to the unfounded fears of constituents. Holders of public office are often manipulative and their constituents are often gullible and easily distracted, Kelley believed.

As evidence, the psychiatrist pointed to the careers of such figures as U.S. Senator Theodore Bilbo and Congressman John E. Rankin of Mississippi and Governor Eugene Talmadge of Georgia. These segregationist politicians of the 1940s exploited racial myths “in the same fashion as did Hitler and his cohorts,” Kelley wrote. “They use racism as a method of obtaining personal power, political aggrandizement, or individual wealth.”

Few overtly racist candidates now remain in the U.S. because the political benefit of espousing such beliefs has vanished. But Kelley would today find the same threat in candidates who use positions on immigration, medical care, school curricula, reproductive rights, firearms legislation, and marriage rights to separate Americans into mythical categories of “us” and “them.” All of these issues carry a powerful emotional charge, and Kelley believed that the manipulation of emotions is a sure indicator of an unworthy, even dangerous, candidate. It’s the sign of an ideological demagogue.

Resisting demagoguery

Kelley considered the political situation in America far from hopeless. To combat the threat of demagoguery, he recommended removing barriers to the participation of all adult citizens in elections, thus reducing the influence of emotionally volatile voters. He pressed for changes in our educational system to emphasize the practice of critical thinking, which today is touted more as a personal and career skill than a benefit to democracy. But critical thinkers, Kelley maintained, can resist their emotional reactions to make smarter choices in the voting booth.

Finally, Kelley urged every American to refuse to vote for any candidate who made “political capital” of the heritage, morals, or supposed otherness of opponents. He hoped to see voters ignore the appeals of candidates who insist that some of us are less than others. Until our political campaigns achieve this level of maturity, he said, “the United States [will] never reach its full stature.”

Sixty-eight years after this perceptive and alarmed psychiatrist returned from a journey into the minds of his century’s most monstrous political criminals, are we ready to pay heed to his advice? Can we become better voters and learn to distinguish good candidates from bad ones? This upcoming election is a good time to find out.