At a Convention of Hypnotists

This past weekend, The Guardian of London published an excellent article by Vaughan Bell on the resurgence of hypnotism in the treatment of a variety of behavioral disorders. The report reminded me of an article I wrote six years ago on assignment for Harper’s magazine about the conflicts between clinicians who practice therapeutic hypnosis, lay hypnotists who cover some of the same ground, and stage hypnotists interested only in entertaining audiences. I attended a hypnotism convention, interviewed several hypnotists of different stripes, and underwent hypnosis myself.

Harper’s did not publish my story, so over the next several weeks I will post parts of it here.

* * *

I saw my first stage hypnotism show seven years ago at the annual convention of the National Guild of Hypnotists, and the presenter was the world’s most famous hypnotist-entertainer, Ormond McGill. The author of many books, including The New Encyclopedia of Hypnotism, McGill at 92 may have slowed a few steps on the stage, but he had not lost his ability to charm a crowd. [He died a few months after this convention.] Wizened, balding, and wearing prominent eyeglasses, he was dressed in a velvet suit with a bowtie and vest. He sat on a stool and told the audience that his show’s objective was to teach how to control the mind. Then he got down to business and took volunteers from the audience.

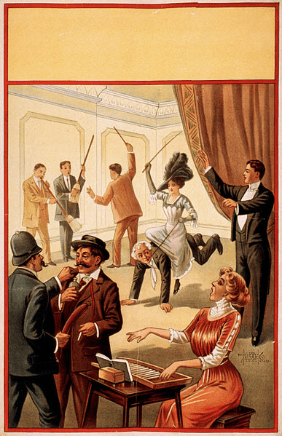

To induce a hypnotic state in his volunteers, he ordered the lights dimmed, evoked Oriental mysticism, and chanted phrases about “the abyss of the inner self.” It all seemed theatrical and old-fashioned, but McGill soon seemed to have his group in a trance. The volunteers complied with his suggestions to move to hula music, pretend to guzzle champagne and get drunk, and dance to the Blue Danube Waltz. He singled out one volunteer and told her to return to the audience and fall asleep in her chair. She slumped as soon as she took her seat.

At this convention, which was held in Marlborough, Mass., the lobby of the host hotel teemed with hundreds of hypnotists, mostly middle-aged people. Some wore suits and tailored outfits that they clearly found uncomfortable, and others gave up any pretense of formality and dressed casually in denim, plain cotton shirts, and sandals. Among both men and women there were many wearers of crystal amulets on necklace chains; the men seemed predisposed to goatees. One of the most devilish goatees was attached to the chin of the late Dr. Rexford North, a founder of the National Guild of Hypnotists, whose portraits filled an exhibit on the organization’s history at one end of the lobby.

Many in attendance were mid-life career switchers: people working in counseling, sales, teaching, and other professions, who saw hypnotism as a skill that could carry them along more exciting paths. I also met clinical psychologists, holders of Ph.D.s, college drop-outs, stage entertainers, psychics, scientists, law enforcement officers, people who perform past-life regressions, physicians, and one woman who brought with her a small dog that she pushed around in a stroller and fed with a baby bottle.

Some of the conventioneers possessed undeniable hypnotic skills. The convention workshops featured repeated instances of participants employing highly creative inductions — the patter and techniques by which a hypnotist places a client into a suggestible state that bypasses the barriers of the conscious mind — that sometimes made the recipients drop into somnambulism within seconds. In controlled studies, hypnosis has helped patients suffering from a wide variety of maladies, including allergies, chronic pain, irritable bowel syndrome, peptic ulcers, hemophilia, headaches, the adverse effects of cancer treatment, tinnitus, asthma, fibromyalgia, and impotence — not to mention a range of psychological problems.

Other presenters put their hypnotic talents to questionable purposes. In one ballroom, a well-known hypnotherapist related her experiences in pulling clients back to past lives as noblewomen, poets, and military leaders. (None apparently had been a peasant, slave, criminal, or common soldier.) Another workshop leader offered techniques to persuade skeptical clients that they had really indeed been hypnotized. But there was little discussion of the hypnotists’ biggest chronic problem, a sense that practitioners with few scruples were harming clients and damaging the reputations of everyone else. Degreed healthcare providers who use hypnotism in their practices — licensed psychologists, social workers, and physicians — feared that uncredentialed hypnotists were treating ailments that required professional care.