The Short and Wondrous Career of Harry Glicken

When I knew Harry Glicken during the mid-1970s at Venice High School in Los Angeles, I could not imagine my classmate as a history-maker of the future. He was disheveled, wore unstylish clothing over his gaunt frame, and had trouble keeping his glasses straight. He spoke in a rush and loved to argue. But to anyone paying attention, which I wasn’t, there was more to Harry than his appearance let on.

Harry was wickedly smart, a true brainiac in a school with quite a few bright kids. He had an off-balance sense of humor, often spiking his jokes with time-release punch lines that took a while to ignite. Harry loved science, and in its interest he could behave with unpredictable enthusiasm: he once brought in fresh human semen to biology lab. He didn’t explain where it came from, and he didn’t have to. That was a memorably awkward moment.

After Harry and I parted ways to go to college, I assumed he’d end up in the sciences and that he’d not likely again come to my attention. I was right on one count and wrong on the other.

Around 1993, I was astonished to hear from a friend that Harry, by this time a volcanologist, had been killed while studying the eruption of Mount Unzen in Japan. I then found out that he had narrowly avoided death eleven years earlier during the eruption of Mount St. Helens. That’s when I realized that I had not really known Harry Glicken at all.

I caught up on his career. Harry earned his undergraduate degree at Stanford University and went on to graduate school at the University of California-Santa Barbara. As a Ph.D. student in the spring of 1980, he began working for the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) to help keep an eye on the volatile situation at Mount St. Helens in Washington. Harry was the sole person manning the Coldwater II observation post just north of the volcano throughout much of May. But he had to leave on May 17 to meet with his faculty advisor. His mentor and USGS supervisor, David Johnston, then temporarily took Harry’s place at Coldwater II.

The next day, Harry heard the news that an earthquake at 8:32 a.m. had triggered an avalanche and an enormous explosion of rocks, hot ash, and molten lava at Mount St. Helens. Coldwater II was obliterated within minutes, and Johnston’s body was never found. Harry, however, did not yet know his friend’s fate, and he found a helicopter pilot willing to take a look. Thick clouds of ash kept the pilot from getting as close to Coldwater II as Harry wanted, so he found another pilot willing to give it a try.

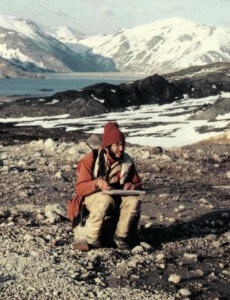

Everything on the ground was desolate. “One wouldn’t know a forest existed here,” Harry wrote. The destruction deeply shook him; he had seen burned people and a dead elk, covered with ashes but still standing. In addition, Harry felt responsible for Johnston’s death. He threw himself into contributing to the USGS survey of the avalanche and became an expert on volcanic debris avalanches.

Harry recovered from the loss of his friend and in 1990 travelled to Japan as a visiting postdoctoral fellow at Tokyo Metropolitan University. Within months, he was close to the scene of yet another eruption, on the island of Kyushu at Mount Unzen, a volcano that had been dormant since 1792. He, along with the French volcanology and photography team of Katia and Maurice Krafft and a group of journalists, was observing the volcano at 4 p.m. on June 3, 1991, when a gigantic explosion collapsed the volcano’s lava dome, started a flow of molten rock, and launched a high-temperature cloud of ash that engulfed the observers. Harry, 33, and his colleagues died instantly along with 39 other people.

Harry and David Johnston are still the only American volcano scientists ever to die during volcanic eruptions. I wish they had no such distinction. If things had somehow gone differently, I would enjoy hearing my rumpled and eccentric classmate, glasses askew, rush through the story of how he survived.

Further reading:

Fisher, Richard Virgil. Out of the Crater: Chronicles of a Volcanologist. Princeton University Press, 2000.

Glicken, Harry. “Rockslide-debris avalanche of May 18, 1980, Mount St. Helens volcano, Washington.” U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, Open File Report 96–667, 1996.

Lopes, Rosaly M.C. The Volcano Adventure Guide. Cambridge University Press, 2005.